Amongst many other accomplishments W T Stead was nominated several times for the Nobel Peace Prize, altered the way journalism operated worldwide and died a hero in the most famous maritime disaster of all time.

W T Stead in later life. Courtesy: The National Portrait Gallery

William Thomas Stead was born in Embleton, near Alnwick on the 5th July 1849. He was the son of the Congregationalist minister there, and W T Stead Road in Embleton has since been named in his honour.

The house in Embleton where William was born -Bailiffgate Collection

A Commemorative plate celebrating the service of William’s father to Embleton : Bailiffgate Collection

The family moved to Howdon on Tyneside when William was very young. He was largely home-educated, including in Latin. His mother Isabella was politically active- undoubtedly having a strong influence on the young William. She campaigned against the government’s Contagious Diseases Act which allowed the police to arrest women purely on suspicion of being prostitutes, even in the absence of any evidence, and subjected them to brutal examination. If found to have Venereal Disease they could be locked up for up to a year, whilst their male clients were left untroubled. The seeds of William’s campaigning spirit were probably set by this initial example of gross inequality.

After two years of schooling at Silcoates School in Wakefield he was apprenticed to a merchant on the Quayside at Newcastle, but began his journalistic career by contributing articles to the Northern Echo in his spare time. In 1871, at the age of just 22 William became the Echo’s editor, the youngest person in the country to occupy that role at that time. Married in 1873 to Emma Wilson, by whom he had 6 children, he continued to work at the Echo until 1880.

Under William’s leadership the Northern Echo soon gained attention as a campaigning paper, at a time when there were many injustices worthy of their attention. Despite the explosion in world power and wealth, Great Britain was a country where the majority of its population lived in appalling conditions, with shocking levels of illness and infant mortality.

With his reputation for campaigning journalism already made at the Echo, William was able to step on to the national stage by a move to London and the Pall Mall Gazette (forerunner to the London Evening Standard), as assistant editor and then editor from 1883. His fearless and forceful campaigning on issues like the scandal of slum housing set a style that may be seen around the world today, no longer just reporting events but going deeper to question whether those in power were acting for the common good. Proof of the power of the new-style press came with the news that the government would set up a Royal Commission which recommended a programme of slum clearance. He was also a pioneer in the incorporation of interviews into newspapers, one with General Gordon of Khartoum fame, and the use of illustrations and photographs.

The abrasive attacks on the establishment were unsurprisingly not universally popular. Sometimes William’s strategies backfired to his critic’s delight. His campaign to eliminate child prostitution went seriously astray when, to prove its existence he “acquired” Eliza, the 13-year-old daughter of a chimney sweep. Although legislation dubbed the Stead Act raised the age on consent from 13 to 16, William was ironically one of the first to fall under its legislation and served 3 months in prison. On a lighter note the story is supposed to have prompted George Bernard Shaw to write Pygmalion, later to become the musical “My Fair Lady”, both featuring of course the character Eliza Doolittle.

Besides campaigning on issues such as child welfare and reform of the criminal code, William also branched out into short stories. By a chilling twist of fate, one concerned the results of a sea collision where there was a shortage of lifeboats, and another where a ship hits an iceberg. With hindsight, his decision to sail on the Titanic (see later) becomes even more tragic.

Resigning from the Gazette in 1889. William’s seemingly unlimited energy turned to publishing, founding the ‘Review of Reviews’, a highly successful magazine with an international readership, designed as a way of binding together the British Empire. Already seen as Britain’s leading journalist, William highlighted another of his interests by founding and editing the spiritualist journal ‘Borderland’.

Travelling to Chicago to visit the World’s FaIr in 1893 and staying for 6 months he was stunned by the level of poverty and despair he found in the host city and published ‘If Christ Came to Chicago’ to try to awake the American conscience. In England again he began publishing condensed reprints of classic literature under the title ‘Penny Popular Novels’, becoming the leading publisher of popular novels of the Victorian era, and pre-dating Penguin Books by many years. In 1896 he launched ‘Books For Bairns’ to try to advance literacy amongst the masses. He attended The Hague peace conferences of of 1899 and 1907 which may be seen as a forerunner of the United Nations, publishing a newspaper of the conferences. He travelled to Russia in 1905 to try to discourage violence during the Russian Revolution-regrettably to no avail. For his efforts William was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on several occasions.

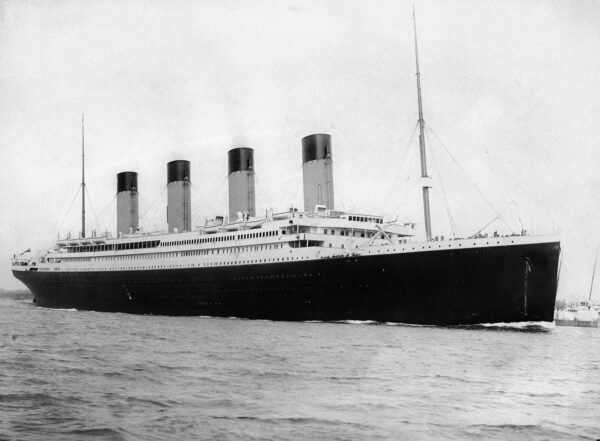

In 1912 William set off to attend a peace rally at the invitation of President William Taft, booking a First Class cabin on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. He is said to have been seen helping women and children into lifeboats and giving his own lifejacket to a passenger without one. His body was never found, although there were reports of him being seen clinging to wreckage until he was too weak and cold to carry on.

Titanic leaves Southampton on its maiden voyage: Wikimedia Commons

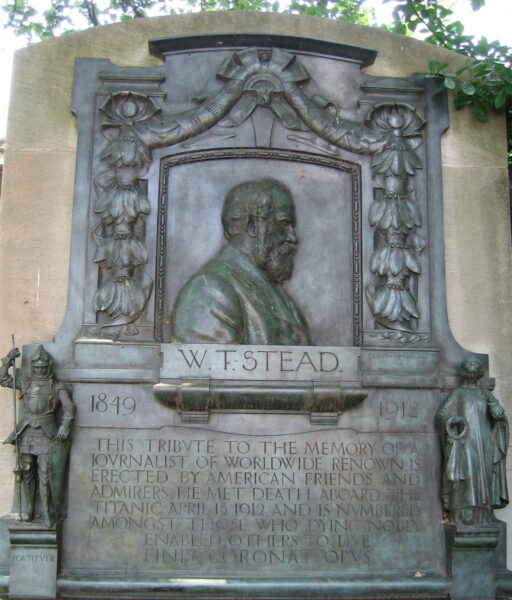

After William’s death the tributes were many. Bronze plaques were erected in Central Park, New York and on the Thames Embankment. One biographer, W. Sydney Robinson said that he had “a genuine desire to reform the world-and himself”. and “He held up a mirror to Victorian society”.

The Bronze Plaque to William in Central Park