Robert Bertram Slack (1886-1913)- Alnwick’s First Sight of Flight

On 2 August 1912 the people of Alnwick witnessed a flying machine for the first time. This was Mr. Robert Bertram Slack on his way to Newcastle. A good view of his aeroplane was obtained as it floated gracefully over Denwick Bridge End farm. Robert was on an exhibition trip around Britain. The 1911 census showed him living in Nottingham with wife Mabel and two children. Unfortunately Robert was not to live much longer although surprisingly, given the high fatality rate amongst aviators at the time, this was not as a result of an aeroplane crash. He was killed on Dec. 21st 1913 in a motoring accident.

Robert Bertram Slack (1886-1913) qualified for his aviator’s certificate on Nov. 14th 1911. In 1912 he was commissioned by the International Correspondence Schools (ICS) to tour around the country giving demonstration flights in a Bleriot Monoplane. He had started in Hendon, and had already visited Leicester, Nottingham, Birmingham, Manchester, Carlisle, and Edinburgh.

A Bleriot Monoplane- as Robert Bertram would have been flying

He was not, however the first man known to have attempted a flight over Alnwick. That honour goes to the indomitable, if eccentric Robert Smart:

Robert Smart (1715-1787)- Our unsuccessful flier

Robert was from Spindlestone near Bamburgh, but his family was from Netherton. Robert was the second son of John Smart. His older brother, William, was heir and became Squire at Trewhitt. His wife Frances was the daughter of William Burrell, vicar of Chatton, and owner of Broompark. Robert and Frances would go on to have five sons and at least five daughters, and lived at Hobberlaw.

Robert Smart’s character

Robert had a reputation for being troublesome, intelligent, eccentric, and ingenious

- He campaigned for a road across the moor to improve access to Hobberlaw – which he obtained. This involved legal action with the freemen.

- He claimed exemption from church rates, but was unsuccessful. This involved legal action with the church.

- He was an amateur mathematician, and astronomer who divided Hobberlaw into geometrical fields – which can still be seen today.

The geometric fields of Hobberlaw on a 19th century map

Hobberlaw from a modern satellite view

- He made an organ and gallery for Belford church (which no longer remains)

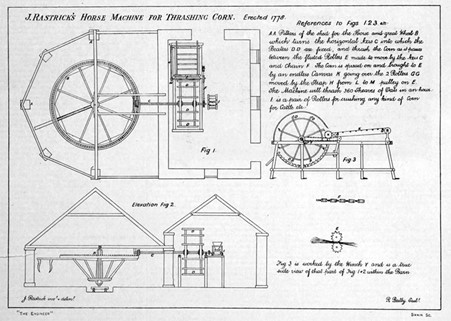

- He invented a threshing machine (about 1778) which rubbed the grain, instead of beating it. Although this was not efficient, and bruised the grain, it did work. However, Robert broke it up because he feared it would take work from agricultural labourers. His servant Rastrick, would later patent a similar machine

Rastrick's Patent

Robert’s greatest claim to fame, however must be his attempt to fly:

The flying machine

Robert believed man could fly through the air like a bird if he had a suitable machine, and made a pair of wings out of leather and feathers. He attached them to his arms with some mechanism to aid their movement and is friends and servants were summoned to witness his first flight. After ascending the granary stairs at Hobberlaw, he waved his wings and sprung from the stair head, expecting to soar upwards. Alas all the efforts he made with his apparatus could not overcome the laws of gravity, and down he ignominiously fell into a gooseberry bush! Fortunately, although the wings did not enable him to rise, they lessened the force of the descent, so that though mortified in spirit, he was little hurt in body by his experiment.

The Lime kilns of Hobberlaw

Funding for Robert Smart’s many adventures appears to have come partly from the income from his lime kilns. An advertisement in the Newcastle Chronicle, 31 August, 1771 says:

To be let and entered upon at Old May-day next, Hobberlaw Farm, within a short mile of Alnwick, consisting of 200 acres of land (a final part only in corn) well inclosed and watered, and in excellent condition. For further particulars enquire of Mr Robert Smart, at Hobberlaw aforesaid. Altogether with, or separate, from the farm, the current-going colliery and limestone quarry, with two large drawkilns on the said farm. The coals and lime may be won at small expence; a great demand of the same. Enquire as above.

When Hobberlaw farm was advertised in 1749, before Robert Smart, it was described as having coal and lime in the ground, but when it was advertised in 1771 it was described with two large drawkilns. This suggests that lime kilns were constructed while Robert was there. This is an earlier date for the kilns than English Heritage give the current kilns.

A lime kiln is used to produce quicklime (calcium oxide) by heating limestone. Kilns would be built near to the source of limestone and coal to minimise transport costs, and away from houses because of the fumes they gave out. There are two broad types of kiln, both are like a wide chimney, often built into the side of a hill. The hill allows the kiln to be loaded from the top and fired and emptied from the bottom. Flare kilns are loaded with a batch of fuel and lime, the fire is burned for several days, then the kiln is unloaded. Draw kilns have a permanent grate over the furnace. They are loaded with alternating layers of limestone and fuel. As the fuel burns the lime drops through the grate, and further layers are added at the top, in a continuous process. Draw kilns make more efficient use of fuel, and produce larger quantities of lime, but this tends to be mixed with ash.

An ancient Lime Kiln

Lime neutralises acid soil, and helps to loosen heavy clay, improving structure and drainage. Demand for agricultural lime increased in the 18th and 19th century. Field kilns such as these would supply a local area (within reach of carts). Elsewhere, in harbours such as Beadnell, Seahouses and Holy Island larger kilns supplied a coastal trade. Local kilns were superseded by large commercial units after the coming of the railways made it economic to transport lime over longer distances. Hobberlaw was still advertising lime for sale into the late 19th century.

With thanks to Alnwick Civic Society for their help in the material for this article.