Present day Food Banks and soup kitchens are a modern manifestation of an ancient impulse to help those in need. This has been recognised as a necessity from at least the early medieval period. Soup and bread were the staple foods provided as they were nourishing and easily made in bulk. This article highlights some of the more socially-aware citizens of Alnwick who were determined to help in difficult times.

A Brief History of Soup Kitchens:

The earliest modern soup kitchens were established in the late 18th century, at a point where several factors, including the Napoleonic Wars, bad harvests, and poor trade, combined to increase the price of food, resulting in increased poverty (does this sound familiar?!). Migration from the countryside to towns and cities in search of work compounded the problem. Feeding and controlling the poor, in the hopes of avoiding the possibility of revolutions, were seen as major problems that required novel solutions throughout Europe.

One of the major figures in the setting up of soup kitchens in Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count von Rumford, a scientist and inventor as well as a philanthropist. Thompson was an advocate of hunger relief. He wrote pamphlets on the subject that were widely read across Europe. His message was particularly well received in Britain, where conditions for the poorest in society were in decline for the reasons noted above, despite an increase in overall prosperity. During his time working for the Elector of Bavaria he set up a workhouse and soup kitchen in Munich, which was copied across Europe, and especially in Britain. It is estimated that 60,000 people were fed by such kitchens in London alone. Soup was seen as cheap and nourishing, and not open to abuse, like the giving of cash was thought to be.

Initially the soup kitchens were well regarded by the upper echelons of society, but they attracted criticism from some for encouraging dependency and for attracting vagrants. They were made illegal, along with other forms of aid, in the Poor Law Amendment Act, 1834.

In February 1847, during the Irish Famine, the British government passed the Temporary Relief Act (known as the Soup Kitchen Act). This act allowed the establishment of Soup Kitchens in Ireland to relieve pressure on the overstretched Poor Law system, which was proving totally inadequate in coping with the disaster. The ban on soup kitchens was soon also relaxed on mainland Britain, though they never became as prevalent as they had been in the early 19th century, partly because from the 1850s onwards, economic conditions began to improve, even for the poorest.

Alnwick Soup Kitchen:

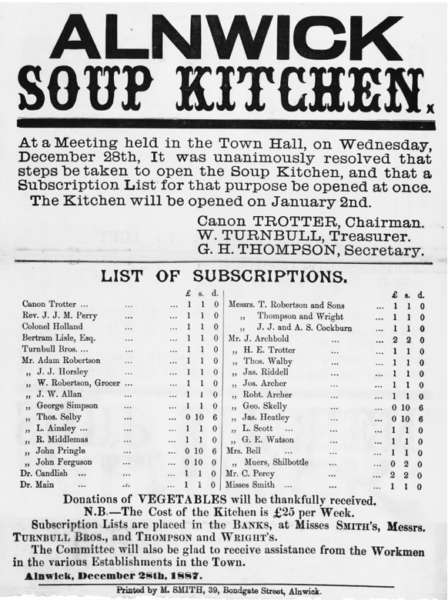

The collections at Bailiffgate Museum includes the committee book, recording the arrangements for organising soup kitchens in Alnwick between 1854 and 1907. The earliest entry, dated January 4th, 1854, refers to the reopening of the soup kitchen, suggesting that there had been at least one earlier soup kitchen.

The Alnwick soup kitchen only operated for a few weeks during the winter months – December to March. It appears to have been opened in periods of severe weather, for instance the winter of 1855 is recorded as being unusually extended and occasionally severe, particularly in February and March. That year the kitchen was opened in late February and ran for 5 weeks. In other years, which may have seen less severe weather, it ran for rather shorter periods. In 1867, for example, it was only open between 17th January and 5th February, recorded as a period of heavy snow. In 1893 it ran between early January and January 25th and was reopened between March 2nd and March 8th.

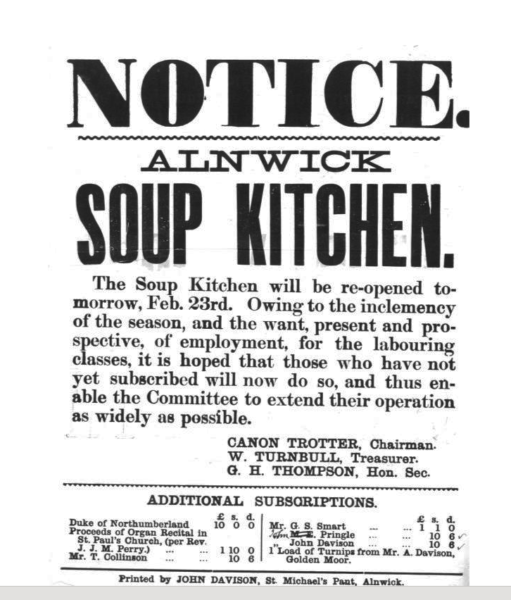

References to changes in the weather, meaning the kitchen either needed to be open for a longer period, or could close early, are also recorded. A committee meeting on 28th December 1882 voted that, based on a change for the better in the weather, that the kitchen should close on December 30th. In 1892 the kitchen was opened on February 23rd, while a committee meeting on March 17th voted to keep it open for another fortnight. However, a meeting on March 24th noted that, owing to a change in the weather, the kitchen should close at the end of the week.

Equally, the soup kitchen doesn’t appear to have been run every year, despite records indicating periods of heavy snowfall, or cold and wet weather during these years. For instance, there is a gap between 1855 and 1860 and another gap between 1861 and 1867.

There is no clear record of where the kitchen was actually located, and it may have varied from year to year. In 1854 a vote of thanks was given to a Mr Johnson for the use of his kitchen. In the 1851 Census there are 2 possible Mr Johnsons. One is Thomas Johnson, recorded as a grocer and tea dealer, living on Narrowgate Street; the other is William Johnson, recorded as an actuary of the Alnwick Savings Bank, who lived at 11 Bondgate Street. Mr Johnson also donated a large pot in 1864, which held 120 gallons. In the same year thanks were given to His Grace the Duke of Northumberland for a room in Bailiffgate Square in which the pot could be placed. A note on the minutes for 1875 states that the distribution of soup will commence at 11.30am, using the entrance by Green Batt.

The soup kitchen was run by a committee of the prominent citizens of Alnwick, all of whom were men. A chairman, treasurer and secretary were all elected by the members of the committee, quite often these were clergymen. In the 1850s and 60s the Rev. Court Granville, vicar of St. Michael’s, was chairman on several occasions. Members of the general committee also formed sub-committees, which oversaw different aspects of the soup kitchen. These included committees to oversee the distribution of soup on a weekly basis, with further committees set up for the purchase of meat, bread and vegetables.

All committee members gave subscriptions to fund the kitchen, but they also appealed for donations of money and vegetables from others, including local shopkeepers. It is noticeable that the minutes distinguish between gentlemen and tradesmen when discussing appealing for subscriptions. Most subscribers gave a guinea (£1 1s), with occasional gifts of 2 guineas recorded in the lists published in the Alnwick Mercury. Although clearly not allowed to be members of the committees, women were allowed to give their mite. A list of subscribers in 1879 included Mrs G.H. Thompson, who gave half a guinea (10s 6d), while a list of additional subscribers, published on December 8th that year, included a further 6 women. The same list records that Mr J.J. Horsley donated one load of turnips and Mr R. Hudson gave a bag of carrots.

Particularly hard times are also briefly recorded in the minutes, with a reference to cases of families affected by fever in December 1882. The committee voted to decide whether to issue tickets to such families on its own merits. Possibly a hint that it was those deemed as the “deserving poor” that received the tickets, rather than the really destitute.

Sources Consulted

Carstairs, Philip (2017) Soup and Reform: Improving the Poor and Reforming Immigrants through Soup Kitchens 1870-1910. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21. 901-936. Available from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10761-017-0403-8 [accessed 25 March, 2023]

Weather Consultancy Services (2023) Weather In History 1850 to 1899 AD. Available from https://premium.weatherweb.net/weather-in-history-1850-to-1899-ad/ [accessed March 25, 2023]