The Davison Bible

William Davison (1781 – 1858) was an important and prolific printer in Alnwick, as well as being a noted apothecary, newspaper producer and philanthropist in the town.

William Davison Mannequin in Bailiffgate Museum

Early Days

Davison was born in Alnwick on the 16th November 1781 younger son of William Davison, a husbandman, gardener and farmer, and his second wife Mary. After his school days, probably in 1795 when he would have been 14, Davison was apprenticed to a Newcastle chemist, Mr Hind. He returned to Alnwick in 1802 and set up business as a pharmacist. For a short time, in 1803, he was in partnership with an Alnwick printer Joseph Perry.

Davison’s more important, though also short-lived, partnership was with John Catnach. This seems to have begun in 1807 with the publication of James Beattie’s The Minstrel and was followed by a collection of Burns’ poems. Catnach had moved his small printing business to Alnwick in 1790. From the mid 1790s, Catnach began using illustrations in his publications and in his 1800 publication of some poems he used woodcuts by the famous engraver Thomas Bewick.

Catnach seems to have had a history of financial problems and this is perhaps the reason for Davison’s short-lived partnership. He left Alnwick in 1808, but Davison continued printing until his death in 1858. His output included the full range of printed material from notepaper and handbills to a range of books including a bible, a prayer book and even a monthly newspaper.

Early in his printing career, Davison began using stereotypes for printing. This involved using a printing plate cast from a mould. He set up a small foundry to produce his own metal stereotypes – some of them made from the wooden blocks provided by Thomas Bewick. In a trade catalogue that Davison produced he advertised for sale a total 1,082 cast-iron ornaments and wood types. Nearly 400 of these come from wood engravings by Bewick or his pupils. It seems that Davison paid Bewick £500 for these.

Throughout his career as a printer, Davison remained an active apothecary and pharmacist and establishing a noted school of medicine. He also became involved in local affairs supporting proposals beneficial to his home town and to its residents.

Printer Extraordinaire

Although only a small town printer, Davison produced the full range of printed material of the highest quality. He was been described as:

“by far the most enterprising printer in the north of England” .

Davison’s interest in printing probably initially stemmed from a need to advertise his own medicinal wares. This may have been the reason for his early partnerships with both Perry and Catnach. As a printer he certainly produced many handbills, posters and leaflets both for his own and other businesses. As already mentioned, it was his (and Catnach’s) early books of poetry with their illustrations by Bewick and others that was to establish Davison’s reputation. These early books included two volumes of poetry by Robert Burns (Davison produced four different editions of these volumes), the popular poem The Minstrel by the Scottish philosopher James Beattie and The Grave by another Scottish writer Robert Blair. These were all well presented volumes as was his most popular publication The Hermit of Warkworth written by Bishop Thomas Percy in 1771 of which there were nine different editions. These volumes were sold for between 5/- and 8/- each.

Davison also publish works by local authors. These were both poetry and prose and included such books as W. H. Brown’s Journal of a voyage from London to Barbados, Andrew Wight’s Life of James Allan, the celebrated Northumberland Piper and a translation by William Probert of the poem The Goddoddin. Again these were illustrated and well-produced and sold for less than those of the nationally known authors.

Another group of books from the Davison presses were school books. There were a number of different textbooks and one of the most successful was The Complete Treatise on Practical Arithmetic and Book-Keeping. Originally written by Charles Hutton, this had been enlarged and corrected by a local schoolmaster, James Ferguson. Editions were published in 1828 and 1835.

The most prestigious publications were the Book of Common Prayer and The Bible. The Book of Common Prayer was produced in 1817 and was a largish book – about 22.5cm by 13cm – with a large typeface something like today’s 14 point. It included an engraved frontispiece with four other plates within the text. For the section on the burial of the dead, the illustration is of St Michael’s Church here in Alnwick showing a view across the adjoining grave yard.

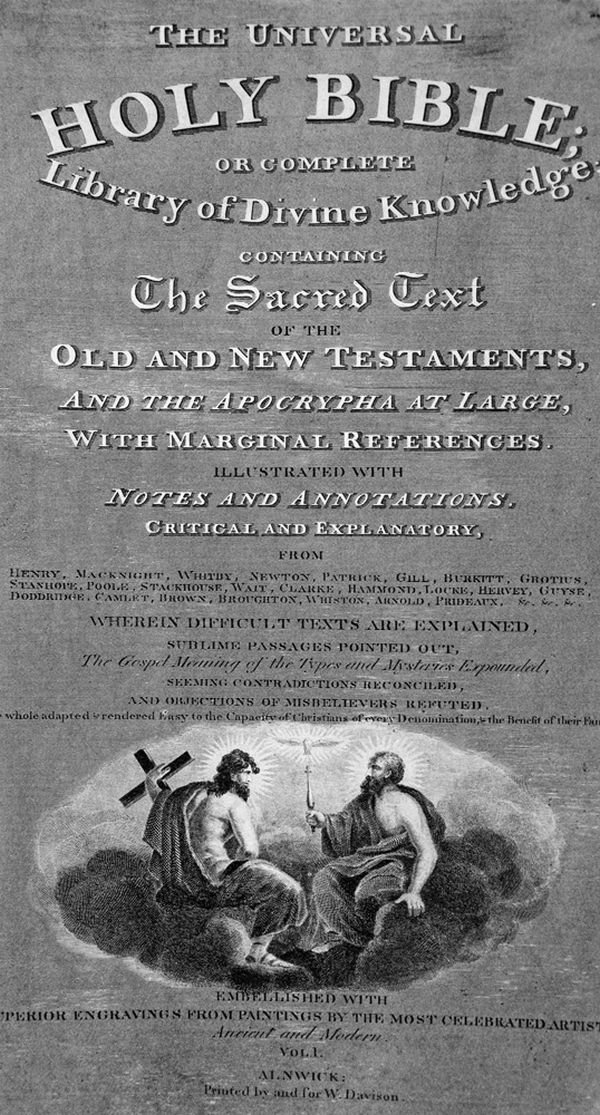

The Bible was an even more ambitious publication. This included not only the full text of the bible but also some commentaries upon it which, according to Davison’s preface, were:

“A judicious selection from deservedly popular and highly esteemed authors … if the notes and recollections selected by the compiler assist in the least to improve the understanding, promote holiness and the conversion of sinners from the error of their ways, he will not have spent his labour in vain.”

The Bible was originally published in 100 parts and sold for 1/- each. It was a huge job for a local printer to undertake – and also lost money. A bound copy of the whole publication was offered for sale at 26/- after Davison’s death.

More popular were his garlands and chapbooks. Garlands were short anthologies of poems or prose while chapbooks were small pamphlets. These were printed on a single sheet which was folded to give a publication of some 8 to 32 pages. The name derived from the chapmen who sold them They travelled around with a large Knapsack selling a variety of publications and other odds and ends.

Davison produced penny chapbooks such as The Amusing Riddle Book and The Book of Monkeys and half penny ones such as The History of Robin Hood or The Anecdote Book: a collection of amusing anecdotes for children. There were also several chapbook editions of The Hermit of Warkworth – these were sold for sixpence.

The Alnwick Mercury

On the 1st June 1854, Davison produced the first edition of his newspaper, The Alnwick Mercury, Northumberland Advertiser and Entertaining Miscellany. A thousand copies were printed and were sold for 1d each. He continued to publish his monthly newspaper until his death four years later by which time the circulation had risen to 2, 600. In starting the Alnwick Mercury, Davison was continuing with the aim that first brought him to printing: advertising his wares. It was to provide, he wrote in the first issue, for:

“the vast amount of advertisements which were now necessary” and “our pages will be enriched with gems of literature of a miscellaneous but instructive nature and entertaining character.”

As with his other publications, the articles in the Mercury were often illustrated with engravings.

After Davison’s death, his son Dr William Davison kept the paper going for a year before selling it to Henry Hunter Blair. In 1884, the paper merged with the Alnwick & County Gazette and in 1900 the firm was purchased by Henry Cheesmond Coates. The merged paper was the forerunner of the modern weekly Northumberland Gazette.

Progressive Reformist

Besides his printing and pharmacy businesses, Davison took a keen interest in local affairs and was particularly concerned to improve the condition of the people of Alnwick. He was always supporting proposals which he thought would be beneficial to the Town.

Davison was one of those responsible for the building of a workhouse for the poor in 1810. This was before the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 which introduced workhouses for paupers throughout the country. He was also responsible for the founding of the Alnwick Dispensary in 1815.

He was also a pioneer in bringing gas to Alnwick. Initially this was in 1817 but this does not seem to have been very successful. However, in 1825, Davison, along with another eight men of the town began with a new works in Canongate which continued to produce gas until 1882 when production was moved to another site in Alnwick.

Davison always showed a concern for his fellow citizens, or as he put it, for the elevation of the masses and the amelioration of their condition. But he recognised that the mission to do this often failed and that:

“the secret of its ultimate success lies with ourselves … with the education of our own minds. “

Many of his great variety of publications aimed at this education of his fellow citizens.

Descriptive and Historical View of Alnwick

One of Davison’s projects that was not completed was to produce a history of Northumberland which intended to publish in parts at 5/- (25p) each. Probably the reason for this failure was the publication at the beginning of the nineteenth century of two other such histories – by John Hodgson and Eneas Mackenzie.

Davison did however produce his book on Alnwick and its second edition was published in 1822. A large part of Davison’s book is taken up with a history of Alnwick Castle and its lords, but the most interesting part today is his account of the Alnwick of his day and his remarks about his fellow citizens, their activities and their entertainments. As a history of Alnwick, Davison’s work cannot be compared to George Tate’s more careful and scholarly work written nearly half a century later but as a description of his times it is delightful.

The Davison Bible – Access for All

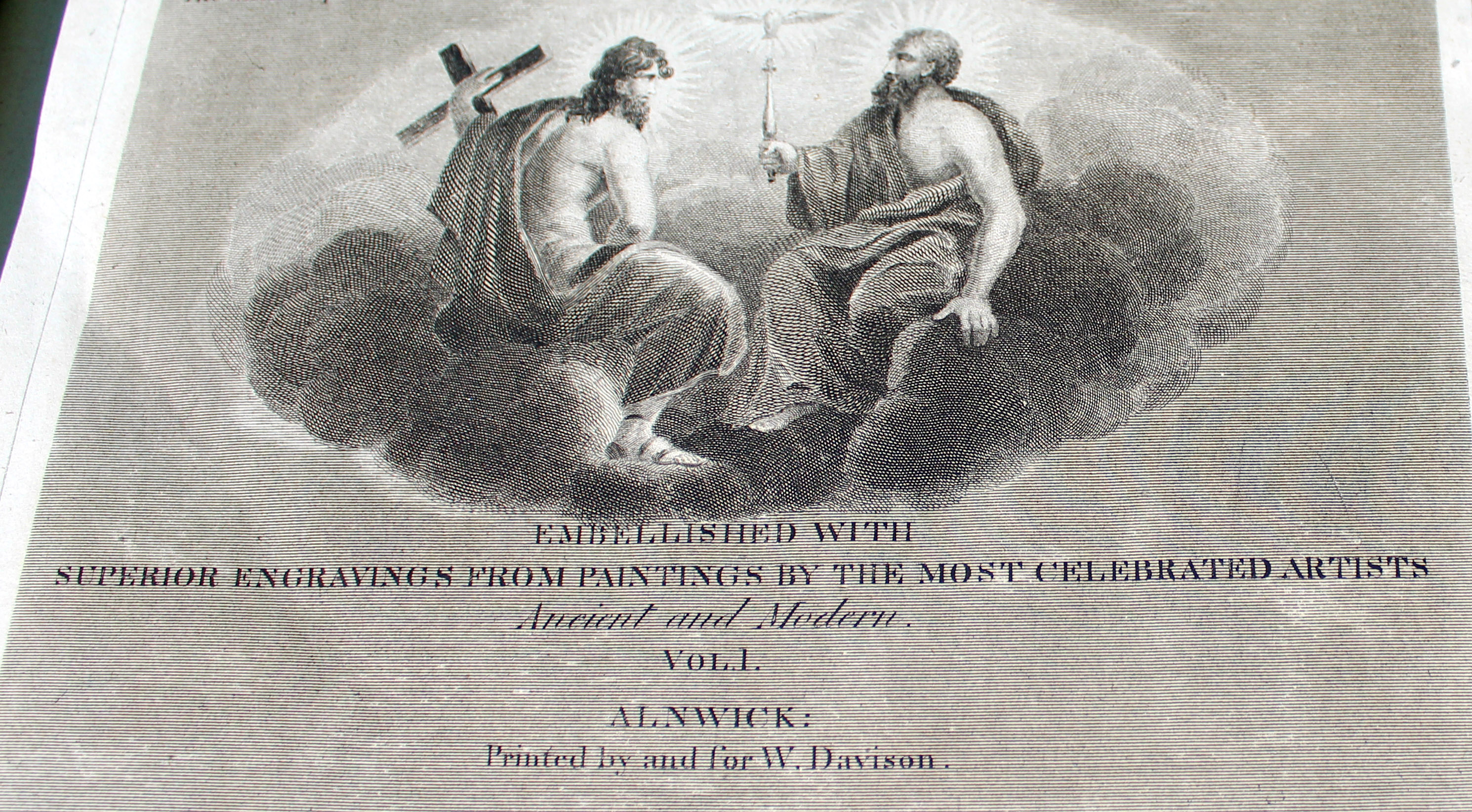

Davisons desire to increase and support Christian learning led him to develop an innovative approach. Rather than solely print The Bible in its entirety, his Universal Holy Bible or Complete Library of Divine Knowledge was published in 100 parts at 1 shilling each. This enabled it to be more widely available to people. A complete bound copy of The Bible (complete with 49 engraved plates) cost £2. 2s.

One problem with displaying books in a museum is that only one page can be open at a time and, though our Davison Bible is normally open to display one of the many engravings, the others are not visible. Now, if you visit our Artworks Section, you can see all the engravings. To the best of our knowledge they are all based on previous paintings from the 16th to the 18th centuries but unfortunately the original artists are not credited in the Bible. Online research has enabled us to identify some of the original paintings from which the engravers worked. The engravers, however, did identify themseves at the foot of each engraving. Most of the engravings are the work of Edward Mitchell (1773-1852) who was a well known Edinburgh-based engraver at the time the Bible was published. Two of the engravings are by James Kerr who had produced other engravings for Davison before the Bible was published.

The Bailiffgate Museum is proud to have a copy on display in our museum as part of our feature on the life and work of Wiliam Davison and for this to have been chosen as one of the “Top 100 Objects in the North East” during the “History of the North East in 100 Objects” in 2013

Davison died in 1858 and is buried in Alnwick cemetery.