“What I Learnt in Lockdown” was a virtual email discussion held by the Alnwick Branch of the NDFHS (Northumberland and Durham Family History Society) in April 2021, after an unprecedented 12 month period of enforced isolation for its members. Below is offered an interesting mixture of the returns:

Bomber Boys

Above : Airmen including the crew of the Lancaster lost on 27th March 1943

During lockdown the end of World War Two, 75 years ago was commemorated. This seemed an opportunity to research a family member killed whilst serving in the RAF. I wanted to hopefully find the families of other crew lost with him. Flight Sergeant engineer Bill Schultz was part of 44 Rhodesia Squadron who flew board a Lancaster Bomber along with six other young men all in their twenties. Their flight left Waddington and they were all killed when their plane crashed over Berlin on the night of 27th March 1943. The cause of the crash is unknown and they lay buried together in a military cemetery in Berlin.

Bill, from Wales was only twenty two when he died alongside five of the crew from Canada. His father had from fled Russia to Canada before WW1 and then joined the Canadian Expeditionary force. This may have influenced Bill to fly with the Canadian crew.

I did successfully trace the seven crew on board and was lucky to find the family of Flight Sergeant Horace Herbert Clements the air gunner onboard. He came from Nova Scotia and was twenty six years old. They kindly sent me a picture of the crew (above). Horace is on the back row second in on the right and Bill is at the far end of the row.

There is a stained glass window in Lincoln Cathedral in memory of Bomber Command.

Useful references

www.cwg.org – The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial

Fights for Rights

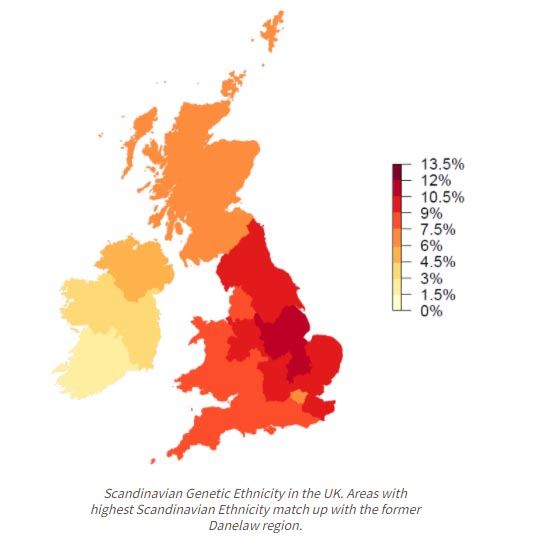

A cartoon of the Friars Goose riot ( Source British Museum)

During lockdown I’ve been researching my three times great grandfather Stephen Crozier. He was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment in Durham Gaol for riot and assault in July 1832. The story behind the riot gives you an insight into the life of a pitman. It was extremely harsh- yielding pitiful rewards in exchange for long hours of dangerous labour.

Pitmen were obliged to sign a bond by which they were forced to remain at a particular colliery, and they were paid not in cash but, in “Miner’s Bonds”. These were vouchers that were valid only in company stores at unfavourable terms. After 1809, the annual Bond was usually entered into on 5th April when a colliery official would read out the rate of pay and the conditions available at the pit. Those who signed up were given a ‘Bounty’ of 2s 6d to start work. If anyone broke the bond, he was liable to arrest, trial and imprisonment. If he attempted to improve conditions or unionise other miners, the law was against him.

The number of notices in local newspapers placed by colliery Masters’ grew, offering rewards for knowledge of the whereabout of runaway miners, threatening to prosecute anyone who employed them. Eventually conditions for coalminers became so intolerable that the workers were driven to unite. Most, but not all of the Northumberland and Durham miners went on strike in 1810. It took the Masters seven weeks to starve them into submission. The ringleaders were arrested, and their families evicted by bailiffs guarded by troops.

Over the following two decades appeals to reason and justice went unheeded and discontent kept boiling up in strikes. An attempt was made at the new Hetton Colliery in the early 1820’s to create a union but it was crushed by the owners and its leader compelled to emigrate to America. By 1832 industrial relations between pitmen and coal owners were at an extremely low ebb. The miners had no union and were determined to form such a group to press for better conditions of employment. A strike lasted from March to August 1832, when pitmen refused to sign the bond prompted the owners to declared that pitmen must renounce membership of the pitmen’s union before they could be employed.

The colliery owners, in an attempt to break the union employed men who were not members, known as ‘blacklegs’. Lead miners were moved in to work in the coal pits and at Hetton Colliery, where miners and their families were evicted, a blackleg was shot dead. The unemployed miners were now reduced to a state of desperation, this brings me on to the riot at East Gateshead where my ancestor Stephen Crozier was arrested.

The miners’ houses were the property of the colliery owners and they were needed for the new, non-union, workers. The efforts of the police to eject the striking pitmen from their homes led to several unpleasant incidents, one of which took place at Friars’ Goose at East Gateshead. When special constables were sent to evict miners of the Tyne Main Colliery at Friars Goose, they were each issued with two cartridges containing swan shot. The miners had been urged to keep the peace and behave in an orderly manner, but the attitude of the police and bailiffs was enough to cause riots and bloodshed.

The miners were enraged by the taunts of the police and the damage to their furniture. While the police were in the house of a Mr Carr, they overpowered the sentry of the building designated as the police headquarters and stole their guns. In the ensuing chaos the police were trapped in a narrow lane. Unfortunately, the lane was overlooked by a small hill where some miners stood throwing stones and other missiles. Realising their predicament, the police fired on the crowd and the miners fired back, inflicting several casualties during the police retreat.

Messengers were sent by the police to bring soldiers from nearby Newcastle. The pitmen realised the plan and obstructed their passage as much as possible, so that when the military arrived, accompanied by the Mayor of Newcastle and the Rector of Gateshead, the rioters had dispersed. Not to be outdone, the forces of the law arrested more than 40 innocent people, including three women, accompanied by considerable police brutality.

Newspaper reports at the time recorded the trial and sentence of Thomas Cowell, William Westgarth, Michael Barkus, John Shotton, John Barkus, Thomas Arther, William Carr, George Durham, Stephen Crozier, Adam Guthrie, Abigail Mouter, William Noble, James Nichols, John Worley, Thomas Nichols, John Anderson, Edward Buckan, William Hall, Maria Carr, (out on bail) Elizabeth Laing, and John Mouter. They were charged “on the 17th day of May 1832, with having at Friars Goose riotously assembled together with other persons unknown and cut and maimed with a sharp instrument one Andrew Young, a constable, with intent to do him some bodily harm; and with having assaulted Joseph Palister, William Penman, William Lamb, and Andrew Young, and robbed them of their guns which was the property of the mayor and corporation of Newcastle-upon-Tyne”.

In 1844 the miners were once again on strike in protest of their bond conditions, once more the miners were crushed, and their union destroyed. As part of their punishment a monthly bond was introduced which remained in place for the next 18 years. The idea of the new bond was to rid the owners of troublemakers but in effect it benefitted the miners by giving them greater freedom of movement. As a consequence of this owners could no longer guarantee a stable workforce, as miners were moving every month without notice. By 1863 the owners collectively decided that the annual bond would be reintroduced from April 5th, 1864. The bond lasted for 8 more years until 1872. The prospect of the abolition of the bond paved the way for the creation of the Durham Miners Mutual Association in 1869.

Hard Times

Southwell Workhouse

Many of us who have traced our ancestors during lockdown would have come across a family member residing in a workhouse. My great grandfather Pierce Fitzgerald and his family were sadly one of those families. Pierce was born in Dublin in 1818 and married Rosanna Tommony in 1838 at Penwortham, Preston Lancashire. By 1841 Pierce was working as a bricklayer and lodging with his father Phillip in Liverpool. Sadly, the 1841 census finds Rosanna in Ribchester Workhouse, Preston.

I can only imagine that their early years together were troubled, as in 1849 Pierce Fitzgerald was charged with neglect of his family. The family having become chargeable to the Parish, he was then Committed to the House of Correction for 2 months- sad times indeed.

How harsh was workhouse life? In 1601, the Poor Relief Act made Parishes responsible for poor relief in England and Wales. By 1776 this act had focused on the Instruction of youth, the encouragement of industry, the relief of want, the support of old age and the comfort of infirmity and pain. In contrast the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act created a new poor relief system, this focused on the deterrent of idleness, an attitude which characterised many Victorian Institutions.

Southwell Workhouse, which is the hands of the National Trust gives you good example of how harsh workhouse life was. This austere building was built from prison design and is the most complete workhouse in Britain. Founded by the Rev John Becher and George Nichols, in 1824 their ideas shaped how the poor were treated during the 19th century. The poor law commission used their model to reform the Poor law Amendment Act of 1834.

Whatever the regime inside the workhouse, as some places were better than others, entering it would have been a distressing experience. New inmates would often have already been through a period of extreme hardship. One of the most unpopular aspects of entering a workhouse and part of its deterrent regime was the separation of inmates. Men, women, boys under 16, girls under 16, children under 7 years of age, the elderly & infirm were all separated. With the exception of some contact between mothers and their children, the different classes of inmate lived each in a separate section of the workhouse building. and had virtually no contact.

Inmates generally washed themselves in cold water from a bucket or direct from a hand pump in one of the yards. Baths, if provided were of the portable tin variety with hot water carried in buckets from the workhouse kitchen. All inmates were bathed on arrival but how often baths were provided after that is unclear.

Workhouse Loo’s were fairly basic. The Privy provided one or more seats over a cess pit or tank which was emptied periodically. In the dormitories, chamber pots might be provided or a communal tub which was carried away and emptied each morning. The earth closet which was patented in 1860 deodorised deposits with a sprinkling of dried earth which then produced excellent fertilizer. It proved particularly useful in workhouses in rural areas, or in buildings where no water supply existed. Around the same time the Water Closet with a reservoir of water was also gaining popularity. If a workhouse did provide such a luxurious facility a single water closet would serve a large number of people, it often suffered from poor maintenance or suffered an erratic water supply, so could get extremely smelly!

The workhouse daily routine was one of early rising and early bedtimes with the hours in between mostly occupied by work, mealtimes and religious observances. Food in a Victorian workhouse was very basic, and like many other features of workhouse life intended to make returning to the outside world seem a more attractive option. Up until the 1880’s adulteration of food was widespread. Milk could be watered down, flour could have chalk or alum added to it, oatmeal could be replaced by cheaper but less nutritious barley meal. The system of tendering for supplies made workhouses particularly susceptible to food adulteration, since the lowest tender was usually awarded the contract. Workhouse inmates who had a restricted diet to begin with were especially vulnerable to any contamination of what limited food they had.

In return for their board and lodging adult inmates were required to work 6 days a week. Women were mainly employed in carrying out domestic chores including the daily cleaning of the workhouse, they helped prepare food in the kitchen and laundry work. Workhouses generally had a wash house where the dirty clothing and bedding were washed and a separate laundry room where after being dried the washing was ironed. Females could also be employed in making and maintaining the inmates’ workhouse uniforms, other occasional jobs included looking after the sick and supervising young children if the workhouse had a nursery. Men were employed in a wide variety of tasks, in the early days of the workhouse the work was often strenuous but with little practical value. The work was intended to add to the deterrent character of the institution. Some of the most common tasks were stone breaking, corn grinding, oakum picking and bone crushing.

In Andover workhouse in 1845 an official enquiry was launched after inmates were so hungry, they fought over the shreds of rotting meat left on the bones they had been given for pounding. The resulting scandal led to the task being banned from workhouses and ultimately to the demise of the poor law commissioners. Many of the more progressive workhouses, particularly those in rural areas cultivated the land around the workhouse. This provided useful work for the inmates and supplied the kitchen with vegetables. For the elderly or less physically able a common task was chopping wood which could then be sold to people living in the area.

Any transgression on behalf of the inmate resulted in punishment, this was true of children as well as adults. The normal punishment was the withholding of food. If the crime was deemed severe enough, a punishment cell was available where inmates were locked up for 24 hours on bread and water. In 1839 almost half of the country’s workhouse inmates were children under the age of 16. Workhouses were legally required to provide 3 hours of education each day. Some workhouses were still reluctant to educate pauper children, believing it gave them an advantage over children outside the workhouse.

In the workhouse dormitories beds were usually packed close together, uniforms were stored overnight in baskets under the bed. Bed sharing was common up until the 1870’s, children in particular often had very cramped accommodation. In 1838 it was revealed that in part of London’s Whitechapel workhouse 104 children were sleeping four or more to a bed in one room.

Workhouses were not prisons, inmates could leave after giving a period of notice so their own clothes could be retrieved and administrative formalities carried out. As with entry, families had to leave together so a man could not abandon his family to the union. Inmates could also, with permission, leave the workhouse for a brief period to look for work. In rural areas where work was seasonal, workhouse populations generally rose in winter and fell in summer.

For Rosanna Fitzgerald, my relative life did not get any easier. In 1856 my great grandfather Henry Fitzgerald their 5th child was born in Stockton Workhouse. For the next 30 years Pierce and Rosanna remained together in various parts of the North East, eventually settling in Durham. Pierce died in 1887 in the County Hospital Durham, and was buried in Redhills cemetery. For Rosanna, her connection to the workhouse was not over. I found that she died in 1894 in the Union Workhouse, Durham. She was then also buried in Redhills cemetery.

Henry Fitzgerald pictured above with his wife Annie.

For many of the elderly and infirm like Rosanna, the workhouse was probably where they would spend the rest of their days. In 1929 the New Poor Law system was disbanded, and workhouses were handed over to the local authorities. Most continued as hospitals, or like Southwell as institutions for the poor, homeless and elderly. Victorian workhouses as an institution lingered long in the minds of people, including those who were born long after it was officially abolished.

In a 3-year project, academics from Leicester University and staff from the National Archive have read and transcribed 7,000 letters written by paupers to the central poor law authorities in London. The project entitled “In their own Write” found letters buried in bundles of official papers. Researchers found that Victorian workhouse inmates complained vigorously about everything from the standard of food to corruption they even threatened to go to the press. The letters convey strong emotions which were usually missing from workhouse accounts. The most vociferous poor were in London and industrial cities of the North and Midlands. Most of the complaints were about the drunkenness of staff, the appalling food and the harsh treatment they received. This research project will continue to assess to see if the complaints actually did lead to any improvement in workhouse standards. The documents will then be available on the national archive website. This project will hopefully shed new light on the perception that the attitude of people going into the workhouse was one of giving up. If anything, the letters show how courageous they were to stand up for their rights.

A Real Saint

A St Patrick’s Day parade in Montreal

Talk of St Patrick’s day led me to try to find more about the man behind the legend. Saint Patrick was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the “Apostle of Ireland”, he is the primary patron saint of Ireland. The dates of Patrick’s life cannot be fixed with certainty, but there is general agreement that he was active as a missionary in Ireland during the fifth century, though a recent biography on Patrick shows a late fourth-century date for the saint is not impossible. Early medieval tradition credits him with being the first bishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland. It regards him as the founder of Christianity in Ireland, converting a society practising a form of Celtic Christianity.

According to the autobiographical Confession of Patrick, when he was about sixteen, he is said to have been captured by Irish pirates from his home in Britain and taken as a slave to Ireland. Looking after animals, he lived there for six years before escaping and returning to his family. After becoming a cleric, he amazingly chose to return to northern and western Ireland. In later life, he served as a bishop, but little is known about the places where he worked. By the seventh century, he had already come to be revered as the patron saint of Ireland. Saint Patrick’s Day is observed on 17 March, the supposed date of his death.

Vikings Ahoy

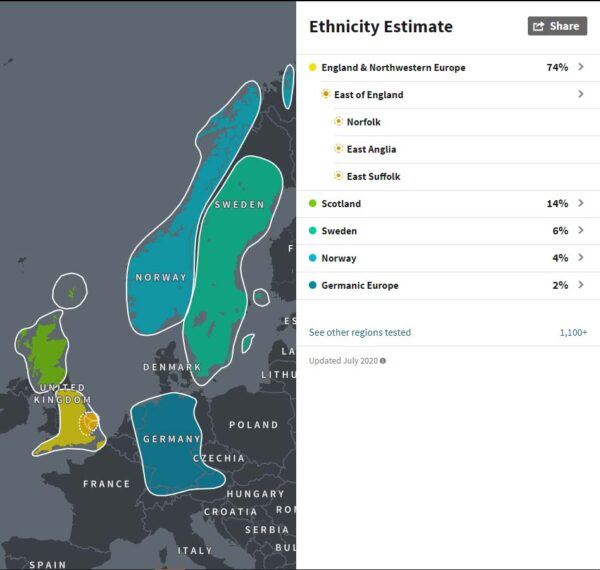

Map showing Scandinavian Gene Presence in the UK (Source Ancestry.com)

A major exhibition on the Vikings will be taking place in Bailiffgate Museum, Alnwick in summer 2021. It led me to an interesting thought during lockdown; am I part Viking?

So many people (especially male) say they would love to have Viking ancestry. I guess it coveys an air of strength and bravery. I am ineligible on those grounds, but I do have other reasons to hope. Conventional research has already revealed that I am a descendent of a Huguenot who, like tens of thousands of others, fled the terrible persecution of their religion that took place in France during the late 1600’s. As my ancestor came from the North West of France, this is precisely the area that was invaded by Vikings several centuries earlier (for example the Normans were Viking descendents).

Researching how one goes about proving Viking ancestry proved a tad frustrating. In fact, there is currently no way of arriving at a cast-iron confirmation. There are however, at least four indicators, which I will detail, so others who wish to can try the tests out on themselves :

- Have a surname with Viking roots?– Examples are names ending in ‘sen’ or ‘son ’, Roger(s), Rogerson, Rendall, Love, Short, Tall, Wise, Long, Good, Goodman, McLeod, McIvor, McAvoy, McAulay, Doyle, McDowell, MacAuliffe, Flett, Scarth, Linklater, Heddle, Halcro. (Source: The Centre for Nordic Studies, Helsinki)

I fail on that one.

- Have ancestors from certain parts of the UK? There was much less movement of families before the early 1800’s. Using online family history research, you should be able to trace where your ancestors lived around that time. The map above shows where Viking Ancestry was most prevalent.

I’m fine on that one, coming from East Anglia back as far as is traceable.

- Suffering from stiffness of your fingers known as Dupuytren’s contracture? (or the less common equivalent in your toes). This is caused by a gene originating from Scandinavia- and is hence often called “Viking finger”.

Not got it- although if you want to see a really serious case look at any Bill Nighy film.

- Had a DNA test suggesting Nordic family origins? Even the basic, and relatively inexpensive Autosomal test may indicate that you have a proportion of Scandinavian ancestry. Ancestry is the main supplier of such tests and appears to have revamped their geographical comparisons since I last checked on my account. The net result seems to have been to show much earlier family roots. When I took it a few years ago, it highlighted NW France, so that supported my Huguenot BMD data. Now the great news is that it indeed indicates Scandinavian roots. Stand back while I don my Viking costume..

The author’s personal DNA Ethnicity Estimate (Source Ancestry.com)

—————————————————————————————————————————–

The Lost Boys

The HMS Acasta Stokers, with Uncle George 4th from left

During lockdown, like most people I decided to have a clear out, and a lot of my VHS videos went to the tip, when it reopened. One video I kept was a tv documentary, recorded in 1978, about the sinking of the Acasta, during WW2. We had this recording transferred to DVD and saw it was better quality than expected, after all these years. The Acasta was sunk by the German ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off the coast of Norway, on the 8th June 1940. My uncle George was a 24 year old stoker on board the Acasta, and was one of the crew killed that day. Some crew members survived for three nights and days in the freezing waters, but when they were eventually rescued there was only one survivor.

George was a career sailor and had joined the Royal Navy in 1934, aged 18. He was promoted to Stoker First Class, and the last entry on his Naval records was, “issued with winter clothing“ on 24th May 1940, followed by his death two weeks later. His mother wasn’t officially informed of his death, however until 30/10/41.

I thought I would try and find out more about the Operation Alphabet that the Acasta was involved in. Acasta and Ardent were in a convoy with the aircraft carrier Glorious , sailing from Norway to Scapa. The operation had successfully helped evacuate British and Allied Forces from Norway, including the King of Norway. The Glorious signalled the Ark Royal asking to sail independently to Scapa, and it was then that they encountered the two German ships. All three Royal Navy ships were sunk, the Ardent at about 17:25 hr, the Glorious at 18:10 hr and finally the Acasta, after hitting Scharnhorst with a torpedo, sank at 18:20 hr. The German ships then left the scene.

No attempt was made to recover survivors. The next day the Southampton recorded in her log seeing bodies in the water, but rejoined their convoy. A Norwegian ship recovered some survivors and took them back to Norway on the 11th June. Over 1500 officers and men lost their lives, including my Uncle George.

I have been in contact with a woman from Portsmouth who is writing a book about some of these events. Official reports on the sinking were stamped “ Closed until 2041” Why is this? Her grandfather was also a stoker on board the Acasta and must have known George. She sent me this photo. Her grandfather is third from the left, my uncle is 4th from the left.

I am also going to ask my grandson to look out the confidential files in 2041. He should find out exactly why our family member died and what exactly the authorities don’t want us to know-then ensure those facts, and Uncle George are never forgotten.

Tombstone Tourist

Devonshire House Picadilly

Lockdown has been an opportunity for any keen Taphophile (aka. “Tombstone Tourist”) to get their exercise by walking around the local church yard. In St Michael’s church yard, Alnwick I found a large, flat gravestone which read:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY

Rebecca Eden

Late of London

Born August 1778

Died July 22nd 1848

I discovered that Rebecca Eden was born to William and “Rebeckah” Eden in Bearsted, near Maidstone, Kent- a mere 345 miles from Alnwick! Nothing seems available of her early life until she is recorded as living in Picadilly, London in 1841. She is there working for Lord Charles Fitzroy and Lady Ann (nee Cavendish). She was aged 60 and a “female servant”. Her position at the top of the census record of servants and her age, however suggests her as having been with the family for a long time, perhaps as lady’s maid.

Lady Ann Fitzroy was born at Haddon Hall Derbyshire, into the Devonshire family of Chatsworth House fame. Their London home was Devonshire House, Picadilly where presumably Rebecca worked. Lord Charles Fitzroy had been an eminent soldier, politician and Vice Chamberlain of the Royal Household to Queen Victoria in 1837. Life in that household for Rebecca was certainly a world apart from Alnwick. “Late of London” on her gravestone is, however now explained.

Sometime in the 1840’s the Fitzroy family move from London, when Rebecca presumably found herself in Alnwick. Her death certificate which recorded her place of birth as Bearsted gave her home address at death as Lisburn Street, Alnwick. Her death was from a “tumour in the side and ulceration of the bowels” and was witnessed by Ann Douglas who gives her address as Dispensary Street. Perhaps Rebecca had been receiving treatment from the Alnwick Dispensary which, although only a cottage hospital had surgeons, a Matron and nurses.

The biggest mystery is why did Rebecca, born in Kent, come all the way to Alnwick? One clue may be that her grave is by the side of those of three other people associated with the Alnwick Castle. As two of the most senior aristocratic families in the land, the Percys -who also had a London town house- would have certainly known the Devonshires, so that may be the link

It’s never enough to just record the facts of someone’s life. This research carries you into thinking what Georgian and Victorian life must have been like for Rebecca. Reading around the period, finding the house someone lived in often puts everything in context and puts flesh on the bones. There is still time, and plenty of material waiting to be brought to life for any budding detective or Taphophile.

Suggested sources:

For an extensive guide to the burials in St Michaels church and churchyard see www.alnwickanglican.com/history/headstones/

www.freereg.org.uk A free site for transcriptions of parish records across the country

Chatsworth online archives includes lists of servants employed by the Devonshires, and much more.

The GRO provides digital certificates online at reasonable cost

“The Time Travellers guide to the Regency period” by Ian Mortimer

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Mapping the Past

I imagine my lockdown experience was very much like everyone else’s; during the first lockdown, the weather was kind, household tasks were undertaken and the garden was well cared for. This latest, winter one was likely to be much more onerous, save for one thing.

The Alnwick Branch of the NDFHS sent out a round robin back in December about something called the Alnwick Historic Town Map Project, and invited anyone interested in participating to come forward. In a rash moment I took one step forward and was pretty promptly approached by the leader of the project group.

The Alnwick Historic Town Map Project is a partnership with the Alnwick Civic Society. Its purpose is “to create an historic town map of Alnwick and Alnmouth, capturing the built history of the town and its port.” A large scale map with overlays of different historic periods and features will be created with the reverse comprising a gazetteer of historic structures. Prior to the Alnwick project the Historic Towns Trust had collaborated only with cities such as Oxford; Bristol; Winchester; York. The Alnwick project was seen as a pilot for smaller historic towns. It will go on general sale in all the usual outlets. The link to the map is here. (www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/content/alnwick-alnmouth)

The project group brings together members from the Civic Society; the Alnwick Local History Society; Northumberland Estates; Bailiffgate Museum, as well as individuals with a general interest in the work. I have been tasked with providing information on schools and religious establishments.

I am now familiar with Zoom meetings, a necessary requirement when face to face meetings are impossible. Drafts of maps are produced, circulated and discussed and data sources shared around the group by a wondrous thing called “Dropbox”. I am now privileged to have access to maps dating back to the 1600s, documents, photographs and paintings, courtesy of the Museum and the Duke’s Archives. How lucky am I!

An early challenge for the project group was to seek funding to allow the providers of digital mapping to be paid. This was the task of one of the Civic Society’s members and we are now in the fortunate position of having phase one of the project fully funded through private donations. Additional funds will go towards developing a second phase.

Not long after the project got underway a member of the Duchess’ School staff joined the team. The two new co-headmasters of the school are very keen to get pupils involved. There are exciting ideas coming out of that relationship.

The link to the map cover on the Trust’s website shows that the project is due for completion in the Autumn. Who knows, with luck and a fair wind, the team might be able to join together for its launch, and even shake hands!

( Images for this page are from personal collections unless otherwise indicated)