A Fortnight in France:

A Soldier’s Story of the Battle of Estaires, April 1918

By David Thompson

Called up on 13 September 1917 Albert Edward Bagley MM was one of thousands of partially trained 18-year-old lads rushed to the Western Front shortly after the Germans launched their Spring Offensive on 21 March 1918. His army service was never discussed with his family but it was obviously a dreadful experience, yet, luckily, he survived unscathed. He was awarded the Military Medal for rescuing a comrade whilst under heavy fire before returning to England because of illness. Shortly after the war, Albert Bagley decided to write a chronicle of his time on the Western Front during the Battle of Estaires in April 1918. With the permission of his son, Harry, in editing the chronicle for publication the author has sought throughout to remain true to the spirit of the original. Unfortunately, so far it has not been possible to establish which Northumberland Fusiliers’ battalion he served with

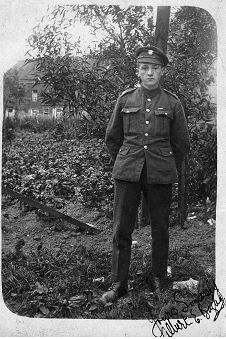

Albert Edward Bagley – Pre-embarkation

After landing at Boulogne, on 1 April, the youngsters of the Northumberland Fusiliers spent three days at Etaples before beginning their journey towards Estaires. They eventually reached what was left of their battalion late in the afternoon of 5 April. The next few days were not happily spent as ‘the old ‘uns’ told of the bad times they had just come through

As they neared Estaires:

‘To our great surprise, coming down the road in the opposite direction were Portuguese Soldiers with no war equipment, and in their bare feet, but some still possessed their rifles and bayonets. Of course, naturally, this set us wondering why they should be coming dressed in this fashion, but however, our thoughts were set at rest within a very few short hours.’

Half-a-mile from the village, the battalion was put into artillery formation and almost immediately the men were ordered to lie down. A shell whistled overhead and exploded amongst a party behind Bagley. The cry went up for stretcher bearers and two casualties soon began their long journey to ‘Blighty’. Just then, an Army Chaplin arrived with information that the Germans had got across the canal and into Estaires

A salvo of shells greeted the battalion as it moved across a ploughed field. For many men, that was their first experience under concentrated shell fire. When a half-finished trench was occupied, Bagley was bewildered as to what to do next although he contrived to dig a hole in the front of the trench, on which he could stand and look over the parapet

Several ‘old sweats’ disappeared over the parapet only to reappear bearing filled tablecloths slung over their backs. When opened the bundles revealed all manner of things including French cigarettes. The booty came from nearby houses. The cigarettes were eventually handed out but, for Bagley, obtaining a light was no easy matter. When he finally did manage to ‘light up’ and inhale, the strong tobacco caused him to cough so violently that he resolved to make that both his first and last French cigarette!

Shortly after dusk the men were ordered to file out of the trench and, after a short walk, to stop, spread out in a long line and to ‘dig in’. After half an hour’s rest, Bagley was gently but firmly stirred from his slumber and ordered to do sentry duty. His only ‘enemies’ were shadows with evil intent. Tree stumps soon developed into Germans in full war paint armed with all manner of ghastly instruments of war.

Moves at night became regular affairs. On that first occasion the men moved for hours and daybreak found them following the man in front, still in total silence. Next morning, a halt was called and the men ‘dug in’ but after only a short rest word was received that the vicinity was no longer safe and it was time to move on. After crossing a few more fields another halt was called and the men were ordered to ‘dig in’, again. Within what seemed only minutes of completing the task they were ordered forward but not without a few murmurings of disbelief and discontent. Bagley noted:

‘I cannot say our mouths were shut now, for there were murmurings as to “Do they know what they want?”, or “What the **** are they playing at?” By “they” the rank and file meant those at the head of affairs.’

During that first morning they ‘dug in’ five times in different places, all within an area of one square mile.

When orders were received to fix bayonets the men did so without troubling to wonder why. Moving on and following the man in front, as usual, the line was suddenly ordered to ‘right turn’, which brought everyone into a long line abreast. As Bagley and the recently arrived men soon realised, this was a planned move which soon met a fusillade of machine-gun fire that momentarily brought them to a standstill but a word from a sergeant behind made them continue the advance. The sergeant’s prompting must have put some life into many numb bodies for everyone started off at a run yelling at the top of their voices. As the Germans retired the Fusiliers found themselves in the open, they pulled up, threw themselves flat on the ground and opened fire. Gradually, the firing died away but heavy firing on their right resulted in an order to retire.

Eventually, the Fusiliers reached the outskirts of Estaires. They walked down the main street only to be caught by machine-gun fire from a side street. Great havoc was caused because it had been so unexpected. Nevertheless, they turned down the street but the Germans decided not to wait but ceased fire and set off for another street in the village. The Fusiliers followed in hot pursuit only to see their prey disappearing over a bridge immediately after which the bridge was blown up.

That put an end to the chase. The men turned back into the main street where various shops and houses attracted interest, for the first time. Bagley observed:

‘It is rather strange how quickly one can forget any exciting, even dangerous, incident, which happened but few minutes ago, if there be something to attract your attention.’

With no movement orders it didn’t take long for the inquisitive to venture inside the shops. Soon, it was ‘standing room only’. Bagley had an alfresco meal of sweet biscuits, dried apricots, prunes and tinned condensed milk. He filled his pockets and steel hat with sweets but on going outside met an officer who promptly told him to put his helmet on. The sweets were only thrown away with great reluctance.

As the men moved off they reflected on the looting of those shops. Their rationale was simple, they had had no food whatsoever for two days and nights. Other articles taken would only have been destroyed by shell fire, and if the Germans got back into the village they would take anything they fancied in any case!

The Fusiliers left the village because the Germans had by now re-entered it and threatened the battalion with encirclement. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies were ordered forward whilst ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies – including Bagley – stayed behind until, an hour later, they, too, were ordered forward to occupy the village recaptured by their sister companies. Within an hour of their last soldier leaving Estaires, the German artillery flooded the place with shells. So many men were lost that it was decided to leave, so ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies withdrew slowly but not before sustaining many more casualties.

After a rest stop the men fell in on the nearby road where they were put into what looked suspiciously like an attacking formation, a fact confirmed within minutes. After walking in single file for about a mile they were ordered to swing round, so that they were once more spread out in line abreast. Bagley and his colleagues soon realised that they were at the front of a brigade attack with the rest of the division acting as reserves.

Within minutes they were greeted with machine-gun fire, which got fiercer as they went on, so much so that the survival instinct caused every man to throw himself down flat and bury his face into the ground. Bagley wondered how long this would last when he felt a tickling sensation under his face. Raising his head as high as he dared, he found the cause was a beetle worming its way between the earth and his face. He recalled:

‘Oh!, how I wished then that I was a beetle, or at least could be so small so that it would be near impossible for a bullet to hit me’.

Immediately following that incident the man about a yard to Bagley’s left – a young lance corporal – suddenly twisted onto his side and in his pain he started to clutch the air with his hand. Bagley had no idea where the man had been hit or what to do. Nevertheless, he edged sideways intending to get the man’s field dressing but as soon as he touched him he clung harder to the ground, so it was necessary to use force to work a hand underneath him. The man began shouting, then begging Bagley to stop. A soldier’s field dressing was in a little pocket on the inside of the tunic, so, lying flat on his stomach, it was hard work to get at it with the wounded man crying out in pain. When he got to the wound safely, Bagley used his knife to cut the man’s tunic sleeve. When the cut was past the elbow, the sight of the flowing blood almost made Bagley sick and he closed his eyes until he had mustered the nerve to carry on. He had never used a field dressing but decided to place the prepared lint and wool on the wound. He could not see the bullet hole for blood, so bent down, screwed his head round and began to lick the blood away, revealing two little blue holes at the elbow. A crude idea of ambulance training told him to bandage part of the arm above the wound and tie off as tightly as possible to stop the flow of blood from the heart to the wound. After giving the man water to cool his throat, Bagley crawled from side-to-side to undo the man’s equipment bit by bit. At that moment the company was ordered to advance. Bagley never found out how the poor boy fared.

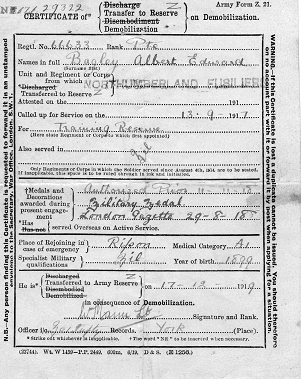

Albert Bagley’s Military Medal Award Card

Having advanced no more than ten yards Bagley felt a thud but took no notice and went on. A few more yards with the bullets still flying hard, the Fusiliers were ordered to kneel and open fire. Bagley picked out one German for attention, took aim and pressed the trigger but nothing happened. Thinking his ammunition faulty he drew the bolt to eject the round, took aim again and pressed the trigger. Still no result! On examining his rifle he noticed a piece of the wood chipped out and when he drew the bolt a second time to examine it he noticed what looked like steel shavings inside. He then realised what had been the cause of the ‘thud’; his rifle had been hit. Had the bullet been three inches to the left it would have shattered his thigh.

With the battalion in danger of encirclement, a retirement was ordered. The men didn’t need to be told twice to fall back but instead of a retirement the withdrawal developed into something of a rout during which lots of men took their equipment off and threw it away enabling them to run faster – Bagley had kept his equipment on reasoning that if a bullet was coming at him, it may hit part of his equipment and, perhaps, lessen its impact on his poor body but he dropped the useless rifle in his hand. It is worth remembering here that most of the ‘men’ were boys just like Bagley, all between the ages of 18 and 19. As Bagley was to record later:

‘If these young boys did nothing else towards winning the war in this engagement alone, 800 of them out of 1100 sacrificed life or limb in stemming the advancing tide which had commenced to role on March 21st 1918.’

This was only their third day in action and about their tenth day in France. In the chronicle there then follows a guarded reference to an incident which Bagley did not wish to relate. There is absolutely no indication of what transpired during the afternoon and early evening of that day.

A few hours after rejoining his unit in a trench orders were received to file out. At about 2:00 am, during a rest stop, the commanding officer asked for volunteers for a scouting party. Having heard a ‘sweat’, a couple of nights before, saying ‘Out here, de as yoor telt, but volunteer for nowt’, Bagley remained silent. When only sixteen men volunteered the CO ordered a number of others to join the volunteers. Bagley – now in possession of another rifle – was one of them.

An officer led the scouting party away up the road but soon cut over fields where the party came under fire from the left. The men were in single file and every so often someone was hit but none too seriously. About ten minutes after the party passed beyond range of the firing the quietness was once more broken by firing from the right, which indicated they were between the two opposing sides, each of which was taking them for the enemy. The men were then ordered to lie down, as quietly as possible. After another fusillade of firing from the right, the officer called out ‘Hullo there, who are you?’ and everyone was surprised and annoyed to hear the word ‘English’ come across the now silent fields. An exchange of questions and answers led to the officer getting up and ordering his men to follow. When they reached what turned out to be outposts of a battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, suitable apologies were forthcoming for their part in the wounding of one man. Bagley recorded that the Durhams demonstrated some poor shooting compared to that which came from their left which had hit six men under similar conditions.

The scouting party moved on to reach a farm house surrounded on three sides by a hawthorn hedge.

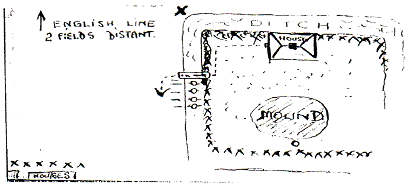

Sketch map of the farmhouse

The men were ordered into an almost dry ditch:

‘The exact part of the ditch we were in is shown by four rings on the ditch. We had not been in this very long when daylight began to appear. Of course we began to talk as soldiers will and the main topic was “What the deuce are we in this ditch for?” but as no answer was forthcoming the subject was dropped.’

Bagley woke with painful limbs after two hours sleep only to realise that the men on either side were still fast asleep and that altogether there were only five of them which led him to conclude that the rest had left quickly because Germans were in the vicinity. A quick check through the hedge confirmed this:

‘One of the follows raised himself slowly up and peered over the top of the ditch and just as quickly lowered himself, and informed us that there was a line of “square heads” on our left (These are shown by crosses at the left hand corner of the sketch). I then endeavoured to get through the hedge to see what was what on the other side. After pricking myself many times I got my head and body half through, but sufficient to see. I was just going to retire when I happened to look to the right where I saw a “square head” peering over a mound inside the paddock I got back into the ditch and informed the others, and if you look at the sketch you realise, like we did, that if we got out of the ditch on to the level ground the Germans on our left would see us, also, if we got through the hedge the gentleman behind the mound would see us and give the warning. We concluded that we were just about boxed and that our only chance was to lie low all day till dark and then make a dash for it.’

Only seconds later, footsteps were heard nearby and concern heightened as someone crossed a plank over the ditch. Bagley was crouching low, frightened to look up but loud shouting from above was followed by a blow on the head. On looking up he saw three Germans shouting and waving their arms. It dawned on him that they were shouting what sounded like ‘Prisoner’.

The Germans were standing over the Fusiliers rifles. Although he knew the game was up, Bagley didn’t put up his hands even though the other four had. Whether the Germans were vexed with him for this he did not know but one of them took out a revolver, aimed it at his face and fired. Luckily for him the German was a bad shot; his face was less than two yards from the revolver but the bullet missed. Bagley seized his chance and jumped up. Grabbing a rifle which lay between the feet of one of the Germans he raised it and fired, striking one of them. At this the other two turned and ran. The other four Fusiliers took the opportunity to pick up their rifles, climb out of the ditch and run in the opposite direction to that which the two fleeing Germans had taken:

‘Just as we reached the corner of the hedge (X at the top left hand corner of the sketch) we were greeted with a fusillade of machine-gun fire, which, unfortunately, hit the last chap as he turned the corner, for he fell into the ditch dead.’

Here the ditch was half-full of water but the men jumped in and kept low for protection. The machine-gun fire ceased only to be replaced by fire from one of the windows of a nearby house occupied by Germans.

The only way the group could let the British know that they were on the ‘same side’ was for Bagley to wave his steel helmet backwards and forwards on his rifle. When nothing happened they took a chance, sprang out together and ran as hard as they could over newly-ploughed ground. There were two fields to cross to reach the British lines. The Germans in the house opened fire with a machine-gun when the party was about halfway across the first field. Nobody was hit but it spurred the men on to make an extra effort to cross the first field, which was divided by a water filled ditch. They had no hesitation about jumping in but Bagley felt himself going down and wondering how far he was off the bottom as the water reached his neck. Just as it lapped his chin his feet touched solid but it was only momentary for he could feel himself sinking in soft mud. Fortunately his feet found a large stone and he managed to balance himself by resting a hand on the bank

When all regained their breath they scrambled out and made another bolt for it but it was more difficult than before as their clothes and equipment were heavy with water. Hardly had their heads appeared above the level ground than the Germans opened fire again but they went as hard as they could passing wounded ‘Tommies’ lying in the field. When about twelve yards from the little trench they had been making for, Bagley’s strength gave out and he had to walk. The other three ran on, reached the trench, then urged Bagley to run but he was too spent to bother much, for he threw himself down on the ground behind the trench unable to move. A corporal leant over and pulled him in whereupon he promptly fell asleep:

‘I woke up with an awful hunger, the like of which I had never experienced before. I asked one of the chaps to undo my haversack which was on my back. He did, and gave me the loaf we had had issued to us the night before. To my dismay it was like a piece of paper pulp, but it didn’t remain whole, for I ate it ravenously but it needed no chewing. This was the first food which had passed my lips since the morning we left the village and dumped our packs on the transport wagons, three days ago, and had been on the move all the time except the two hours sleep I had just had when pulled into the trench.’

Albert Edward Bagley shortly after being awarded the Military Medal, possibly taken in France

Bagley and his three mates found that they had run into Grenadier Guards who had been sent up during the night to in an effort to hold the German advance and, of course, they were sincerely sorry to hear that one of the Fusiliers had been killed. The trench was occupied by seven Guardsmen plus, then, the four Fusiliers. Nothing much happened until late afternoon when three Germans were seen crawling towards the British trench. The corporal gave orders to ‘see them off’ but not to waste ammunition as there was none to spare. As they got up and leant on the parapet they were greeted with such a volley of machine-gun fire that they immediately ducked back under cover. The three Germans started to ‘dig in’

The Grenadier Guard on Bagley’s left raised himself to the parapet and took aim but he didn’t fire, for he fell back into the bottom of the trench. Bagley stooped down to get the man’s field dressing when his eyes wandered to the back of the man’s neck where, just above the coat collar, was a tiny blue hole turning red as blood oozed from it. Bagley turned sick and faint when he realised the man was dead. He picked up his rifle intending to shoot at the Germans but another hail of bullets made him duck. This happened again before he could get a shot away. When he did he was surprised to see the German in the centre jump up a little, then fall flat.

After settling the fate of the three Germans the men settled down and had a quiet fifteen minutes cleaning their rifles. Bagley was ordered to take ammunition out of the dead man’s pouches. As he undid the first pouch blood dripped onto his hand, which caused another spasm of faint-heartedness but he stuck at it and managed to get all the ammunition available. His hands were covered with blood, which remained engrained for days

Half an hour passed when suddenly the atmosphere was disturbed by heavy machine-gun fire on the left. Thousands of Germans were seen making for British positions from whither came heavy firing in an endeavour to stop the advancing crowd. The men eagerly watched the Germans’ progress but in spite of huge numbers falling down the majority kept on their course until finally the leading ones were hidden from view by the trees of a small wood. To their dismay the firing got less until finally it ceased and they realised that the Germans had gained their objective

The men soon saw Germans working through the trees in their direction. An intervening outpost was quickly over-run. Outflanked, the British could bring very little fire to bear and when only a few yards separated the leading Germans from Bagley’s trench, the corporal gave orders to leave but for the two end men to remain till the last and keep up their firing. Bagley:

‘…was handed two panniers of machine-gun ammunition to take care of and presently it came my turn to get out of the trench and crawl away. We had to crawl because the moment the first man got out of the trench our old friends in the house directly opposite turned their attention to us once more. Out on the level ground we had not the protection of our trench and this we knew for the bullets were playing round at a most uncomfortable nearness. The chap crawling behind me was unfortunate, for he was hit in the leg, but he continued to crawl after me. For myself, I was just about strangled as the two panniers were dragging on the ground and the straps round my shoulders had slipped onto my neck making breathing rather a hard job.’

First one, then another member of the party was hit. As they neared their goal only the corporal was in front of Bagley, dragging a Lewis Gun with him. With only four yards to go the corporal was level with a small pond when he reared over. Without a word he pushed the Lewis Gun towards the pond before crawling round the corner which prompted Bagley to put on an extra spurt only to round the corner to find the corporal pressing himself hard against the wall. Bagley guessed what was wrong but he was waved away

Presently all the men reached the corner. Only six of the seven Grenadier Guardsmen and one of four Fusiliers remained with only one of the seven survivors unwounded, Bagley. They started to walk down the road, helping each other as best they could. They hadn’t gone far when they heard shouts from the field on their right. Crossing over and getting through the hedge they saw a number of ‘Tommies’ facing the Germans who had now got onto the road they had just left. They opened fire and swept the leading Germans off their feet, the others threw themselves flat on the ground. Gradually the British fire slackened and some of the Germans decided to make a dash for it but the British were watchful and before the first German was properly on his feet there was a fusillade of bullets and he fell. This discouraged others from risking it. Presently the Germans began to work their way backwards and when they thought they were out of immediate danger they got onto their feet and bolted for a distant group of trees

After an hour’s rest, the men moved off in single file across the fields as dusk fell. At the first halt they collected into groups each of which was briefed by an officer who said:

‘“Well boys things are pretty bad just now, but I don’t want you to “get the wind up”. I am going to trust you to see the job through and it consists of this. At the moment there is a gap in the British line and you fellows are the only ones at the present to fill this gap. There are not sufficient numbers to fill the gap with the usual number of men, therefore, you are to be spread out so as to cover the distance, but to make the best of a bad job you will be in pairs”.’

They moved on slowly whilst every few yards pairs were left to ‘dig in’. When their turn came, Bagley and his mate began to do so with unusual vigour but their efforts made little impression and gradually slackened. They were delighted to learn that a company of Royal Engineers was coming to dig their holes for them. They had not long to wait and gladly vacated their 9”-deep hole to let the new arrival get his job done.

While the engineer worked, Bagley slept and woke to find all quiet with the hole-digger gone. His mate was already in the enlarged hole – only four feet long, just over two feet wide and about three feet deep – and fast asleep. Bagley was in within seconds. To keep awake he started digging to deepen then widen his end of the hole. It was slow work but, eventually, he formed a seat on which he could sit properly and comfortably

When his mate was roused from his slumbers, Bagley managed to get some sleep but it was not long before a ‘stand to’ order was received. He had just got his wits together, fixed bayonet and had his rifle on the parapet when firing commenced. He fired about ten rounds before it died away and above the rattle could hear voices shouting, ‘Stop, Stop, we’re English’, the call came that they were ‘Coldstream Guards, Second Battalion’. Bagley and his mates had killed a good few and wounded a lot more. The Coldstream Guardsman who joined them in their hole explained that the Coldstreams’ had got lost and were waiting for daybreak to get their bearings. Eventually, they moved on

At 10.00 am, next morning, the outposts were greeted with a hail of bullets from a house directly opposite, and every so often their line was swept by machine-gun fire, the bullets passing only inches overhead. Bagley:

‘…then busied myself with trying to plan some way of having a good shot or two. I told the other chap to bore a hole through the parapet with his bayonet, and I commenced to do likewise, but when my bayonet was in up to the hilt I had not succeeded in making a hole right through. I then got a cartridge and pushed it into the barrel of my rifle, bullet first, so this would prevent my rifle getting choked with clay, and then proceeded to force the rifle through the hole I had started with the bayonet. At last I got right through, and then worked the rifle up and down which made the hole slightly bigger.

Just then my pal completed his hole, and I explained what to do. I told him that whilst I fired, for him to observe through his hole the effect, so that I could correct the mistakes whilst neither of us were exposing ourselves, except that a bullet would have to come direct through the hole to be dangerous, and then again there was very little room, for the rifle filled the hole and there was only about half an inch of space which would take some hitting from such a distance.

Having placed my ammunition handy I commenced operations, at first, I waited for my pal to tell me from what point of the house the Jerries were firing, and when the next burst came he soon saw that it was a small window in the roof, which, by the way, did not slope all the way, but just half way, and then the slates were flush with wall. The next time the Jerries started their machine-gun I had a few shots and then waited till they ceased, and then my pal give me instructions as to my firing. The next time the Jerries opened fire I also put in a few more, and asked for information as to results which I was informed was all right in direction, but just too low. It was hitting the top of the wall instead of the plates.

I did not fire whilst the Jerries ceased their methodical bursts, so that whilst they were firing they would not notice from where my bullets were coming. Once I got on to the window. The third time proved ‘catchy’; for when they started so did I, and my pal whispered that I was correct. At that I wedged my rifle with clay and waited for them firing again. I got more ammunition handy so as to be ready to put in a good load of lead.

I was also getting rather excited as I knew all our fellows were watching the affair very keenly. At last, what seemed ages, the Jerries started again, thinking that the last few bullets were stray ones, no sooner had they got going than I started trigger and bolt. After 35 rounds I stopped as my rifle was too hot and on asking my pal what the result was he said that he saw two men actually drop. I then started again and had only got fifteen rounds off when suddenly their machine-gun stopped firing altogether. I continued firing for a short while, then ceased and pulled my rifle out to see for myself, and to my surprise, could see daylight right through the roof.

Just then someone shouted “There they are”, and, looking up, I could see three or four bent figures appearing from the back of the house and running along the road. Our chaps opened fire, but the figures were lost to view behind the mounds. However, I was satisfied, for it had been mere sport and had passed the time fine. Once more quietness reigned, and we talked of the late happenings we had just enjoyed.’

Sometime later Bagley looked to his left only to see hundreds of German soldiers. A sudden fear came over him as he realised the hopeless position they were in. The information quickly passed down the line but the Germans did not seem much concerned with the immediate future, for they appeared peacefully resting behind machine guns trained on the British outposts. Soon, a NCO crawled along the line of outposts and as he passed Bagley’s told them to vacate their positions and make a dash for freedom.

The Germans who were on their original front opened fire on the men as they crawled along but their bullets were just too high and flew straight on and went amongst the Germans who had succeeded in getting to the rear of the British positions. As this firing increased in volume, it caused panic amongst the Germans to the rear such that they started to frantically wave their arms and shout at the top of their voices. Whether this panic amongst the Germans misled some of the British to imagine that the Germans were signalling to them to throw down their arms and surrender or be wiped out, was unclear but Bagley saw lots of men taking off their equipment, raising their arms and advancing towards the excited Germans. He had no intention of hanging around and started to run down the line intending to strike off to the right, the only exit available

The firing from the left was getting worse so Bagley intended to shelter at the next hole until it died down. On jumping in, he found an officer lain half in and half out of it underneath who was another dead officer. He was shocked to see that the top man was none other than the officer who led the scouting party the day previous, which unnerved him. When the firing eased he decided to risk it once more. He started to run and, just as he neared another hole, a sergeant challenged him with ‘Hey lad where are you going? If you don’t stop running away I’ll shoot’. Bagley pulled up, pointed out the Germans and explained what had happened. Hardly had the words been uttered than the sergeant and his mate got out of their hole and made off.

As the three of them ran past the other outposts they shouted what had happened and, soon, a dozen men were making a dash for freedom. The bigger target presented attracted enemy fire supplemented with shell fire. Bagley got short winded and walked for a short time. When he’d regained his breath he again started to run aiming to catch a group of six or seven men who had got further on. He had barely begun when he heard a whistling overhead so threw himself flat on the ground. As he got up to run again, to his horror, the group of men had disappeared. Passing the spot where the shell had burst there were only bits of clothing and patches of blood

After running about two miles he made for a large wood. When only a short distance from its edge, he was surprised to see human faces peering at him from behind a hedge. Just then a figure stepped through the hedge and what a relief it was to see the khaki uniform of a British officer. After explaining what had taken place during the last two hours, Bagley followed the officer to the wood where he found a well made trench, manned by Australians and Machine Gun Corps. He gratefully accepted a meal of bread, ‘Bully’ and cheese. There were few meals he had enjoyed more, and imagine his surprise when putting his lips to the water bottle only to find it contained fresh cow’s milk from a nearby farm

Next morning, he woke, feeling fine, so he sought out the officer to ask what he could do. The officer replied that he really had no need of him but that Bagley could please himself what he did. He went off to help the officer’s batman in his work, then attached himself to a sergeant and took a turn at sentry duty for a couple of hours

Late in the afternoon a stir was caused by the sight of a long line of advancing Germans. Immediately everyone checked his rifle to see it was in good order. Still the Germans came on and orders were received to ‘stand to’. When less than two hundred yards away, the Germans halted and began to ‘dig in’. The officer watched them intently but did not give the order to open fire

When dusk fell the Germans were well under cover. The night was spent closely watching their line and filling extra cartridge belts for the Maxim gun. As daylight broke the British line was bombarded with shells. Generally, the German’s range-finding was bad but one shell landed in the trench and when the smoke cleared up went the cry for stretcher-bearers. Just then a figure scrambled to the level ground and staggered towards Bagley:

‘To properly describe the man’s appearance is well nigh impossible. His face was drawn and haggard, almost green in colour, and as he staggered along his hands were clawing the air in his agony, for his tunic was all scarlet in front. He staggered on past where I was standing, and no one intercepted him, for I think everyone was too horrified to approach him. How he faired I do not know, but hope his agony was ended soon, for he was terrible to look at.’

The greater part of the day passed quietly until about 5:30 pm when, suddenly, the Germans mounted their parapet and started towards the British line. Immediately everyone was on the alert, waiting for the officer to give the word to open fire but no sound came from his lips. The men were anxious, wondering what was going to happen when the officer said in a quiet voice, ‘When I give the word no one except the machine gun must fire’. This did not give much satisfaction but it broke the tension

When the Germans were barely fifty yards away the word came slowly. The sergeant worked the gun calmly from left to right. Every fourth German went down but still they came on, and then the gun slowly started on its return journey and, still, almost every fourth man went down. The German advance did not look quite so determined. As the gun started again to mow from left to right, they wavered despite their officer’s promptings then they all turned and began to bolt. The British riflemen opened fire to encourage them. Straight over their own trench the Germans went and as they retired their numbers got less until very few disappeared into the distance altogether. Like children, the British cheered themselves almost hoarse

As preparations were made for a relief later that night, the Lieutenant sent for Bagley who was given a note to take to his battalion CO, to cover him for the two days he had been with the Australians and Machine Gun Corps. He was told how useful and accurate was the information he had brought with him, which had enabled the officer to come to some decisive conclusions. What was meant by that Bagley never knew!

Albert Edward Bagley, MM, post-Armistice

An hour later, the men gladly handed over their positions to the relieving corps. As he tramped along through the wood, Bagley noticed what a beautiful night it was. His chronicle closed with the thoughts which ran through his mind that night, and the author can do no better than quote extracts from the final paragraph:

‘How lovely those stars were shining as they twinkled so clearly overhead. Not a sound to be heard except the swish of men’s feet in the grass, and oh! how tall and stately were those trees, where now were no lurking shadows like I had previously imagined… I had no thoughts of the immediate future. Why should I? No more war for a few days. How bright the moon was, and only a few hours ago he was almost an enemy to us, but now I could admire him. Tomorrow no war for me, and perhaps the next day… Oh! what a joy to be alive…’

Demobilisation Certificate

END